Author Edward Carey reimagines a time-honored fable: the story of an impatient father, a rebellious son, and a watery path to forgiveness for the young man known as Pinocchio. We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from The Swallowed Man, available now from Riverhead Books.

In the small Tuscan town of Collodi, a lonely woodcarver longs for the companionship of a son. One day, “as if the wood commanded me,” Giuseppe—better known as Geppetto—carves for himself a pinewood boy, a marionette he hopes to take on tour worldwide. But when his handsome new creation comes magically to life, Geppetto screams… and the boy, Pinocchio, leaps from his arms and escapes into the night.

Though he returns the next day, the wily boy torments his father, challenging his authority and making up stories—whereupon his nose, the very nose his father carved, grows before his eyes like an antler. When the boy disappears after one last fight, the father follows a rumor to the coast and out into the sea, where he is swallowed by a great fish—and consumed by guilt. He hunkers in the creature’s belly awaiting the day when he will reconcile with the son he drove away.

He was not got in the usual way, my son. Before I tell you how it happened, let me prepare the ground just a little better: Have you ever had a doll that seemed to live? A toy soldier that appeared to have a will of its own? It is not so uncommon. So then, as you read, if you place that old doll or soldier beside you, perhaps that should help.

So to it:

I carved him. He came to me out of wood. Just an ordinary piece of wood.

I am a carpenter, to be clear. I had long desired to make a puppet, just such a puppet, so that I might tour all the world with him, or earn some little local money, or at least—I should say at most—to have at home a body, some company, besides my own. I had known bodies in my past; I was not always so singular. Yet I never did make a family of my own. Despite everything, despite my pride in my woodwork, despite the solid walls of my fine room, I confess I found my days limited in company. I wanted another life again, to make—as only a carpenter of my skill might make—the sacred human form in wood, for companionship, and to show off without question my very great worth.

I went about it in a creator’s haze, in one of those moments when you are close to the divine, as if something of me and yet something altogether greater were connected to my feeble form as I worked. It was sacred magic.

Before long, I realized that something strange had happened. The first glint came just after I carved the eyes. Those eyes! How they stared at me, directly, with intent. Perhaps I should have stopped there. Yes, I have been known to imagine things—like any other person—but this was different. The wooden eyes held their stare, and when I moved, they moved with me. I tried not to look. Are you, dear reader, an artist, even of the Sunday variety? Have you ever had those moments when, without quite knowing how, your art comes through with more grace, more life in it, than you had supposed possible? Have you wondered what guided your hand as you created this strange, wonderful thing? And have you attempted to repeat it, only to discover that it never happens quite the same way again?

I told you of this puppet’s eyes: Staring eyes, unnerving eyes. But they were my work, after all, so I steeled myself and carved on. Next: A nose. And again, as I carved it, the nose seemed to sniff, to come living before me. To grow, you see, long. Longer than I should have chosen, but the wood, do you see, gave me no choice. It was as if the wood commanded me, not I it.

***

And then beneath, in a fever, I made the mouth. And this—oh, you must believe—this was the point of certainty! For the mouth made noise.

It laughed. It laughed … at me.

Nearly a boy’s laugh, but not quite. A certain squeak to it.

This day was unlike any other.

Buy the Book

The Swallowed Man

I had never yet before made something living. But here it was! I went on, carving neck and shoulders, a little wooden belly. I could not stop. Arms! Hands for the arms! And the moment it had hands, this is the truth, they moved.

Have you ever seen a chair move on its own? Have you witnessed the promenade of a table, or seen knives and forks at dance with one another? A wheelbarrow wheel itself? Buttons leap to life? No, of course not. And yet we all know, we all have experienced, the disobedience of objects. And this object, mimicking as it did the rough shape of a body, presented itself to be a man! Right there and then. Before my eyes. It mocked humans; it mocked me.

Its first action, on finding movement: to pull the wig from my head.

I flinched; I shuddered. But it was too late to stop. I was in a passion of creation—I was under command of the wood—and so I carved on.

I gave him legs. Feet.

And the feet, on divining life, kicked with life. Kicked, that is, my shins.

This terrible thing!

You are an object! I cried. Behave like one!

And it kicked once more, for it was loath to follow the rules of objects. Rather, it threw down the book of rules and stamped upon it.

Oh God! I said to myself, for I was quite alone in my room. What have I done!

The thing moved.

I screamed in terror.

On finding it had legs, the thing had got up. It took to its feet, tested their balance, found them sturdy. And then it walked. To the door.

It opened the door. And then it left.

My sculpture, it ran. Away. The thing was gone.

***

I screamed a moment and then I, too, ran. Terrified of losing it. For the thing was mine, it was my doing, I had made it.

Unlikely, you say? And ye t it is all quite true. As true as I am a man imprisoned inside a fish. I am being honest. I am rational. I am in absolute calm as I write, as I beg you: Imagine having an earthen mug for a son! Imagine a teaspoon daughter! Twins that are footstools!

It—the wooden creature, I mean; I did think it an it to begin with, forgive me—it did not understand. It had no comprehension of the world, or of its dangers. A shortcoming I discovered on the very first night of its life.

***

It had a voice, indeed it did. The next morning, when I returned home, it spoke to me.

Here I must add: That first night of its life, I had been forced to sleep elsewhere.

I had been, that is, locked up. Because I lost my temper.

That first evening, after I had carved it and lost it, I rushed out after it. I looked and looked, wondering at how this stick-thing could have escaped me, at whether what I’d lost was my wooden boy or perhaps, was this the truth, my own mind.

Then at last, in the street, there it was. The sight of it was so strange, so out of place in, of all places, the town of Collodi, province of Lucca. Yet there it was! I wondered how to approach it and settled on the most cautious course: I sneaked up behind it. And then, once my hands were upon it—one round its midsection, one clamped over its gouge of a mouth—I picked it up and turned for home.

But it struggled, the dreadful object. And I struggled, anxious not to lose it again. The wooden thing bit me, and I pulled my hand away. It shrieked out in great complaint. And I bellowed. I … said words. I was upset, you see. I was angry. I own that. I surely mimicked my own father that evening, my own lost father whose shouts still trouble me.

And then people came running and interfering, yes indeed, until onlookers and neighbors became a crowd. And the crowd said I was a mean man, and what awful cruelties would await my poor, though peculiar, child once we were both at home behind closed doors. It was the anger of love and of fear. The fury of protection! And then a policeman added himself to the crowd and put his ears to the situation. He was not without sentiment. And so my son—not fully comprehended in the darkness—was set free and I was taken to gaol. The people, the policeman, they sided with it! With it! It before me!

I was locked up.

Not because I was a precious object, not to keep me safe, but because I was an unprecious object. To keep them safe. And so I spent the night confined. Disturbing the peace. As if my miracle were already polluting the morals of the world.

***

When I was set free that next morning from Collodi gaol—which has but two cells; we are generally a law—abiding folk—I rushed home. As soon as I reached my door, my rage flared up again. I suspected it would be home, I hoped it would be home. I meant to put it right, to make it known that I am a human and it but an object. The door to my home was locked. Indeed, locked by the creature inside.

I banged on the door. I banged on the window, in a fury by then. And looking in at the window I saw it: the carving, my carving! I tugged up the window and crawled in.

It spoke, its first word:

“Babbo!” That is how we say “father” in my part of the world.

Father!, it called me. The effrontery! Me, a real human. This object, this toy. It called me Babbo!

This little thing who refused to be a thing. Living dead thing. How it terrified.

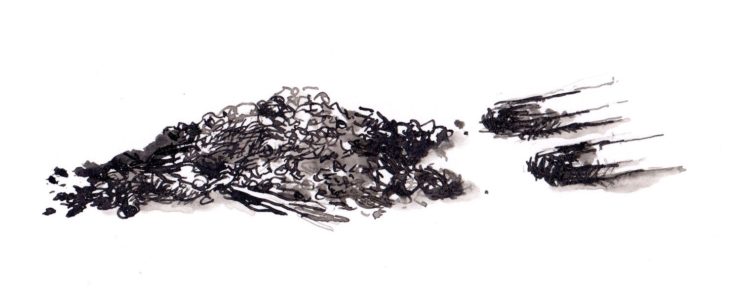

And then I looked farther, down to its feet, and saw it: burnt stumps! It had set fire to itself. The flames were long extinguished, it sat in its own ash.

“You might have burned down the house,” I told it, observing its scorched limbs. “The whole street.”

“I was so cold!” it cried. “That gave me no warmth.” It pointed to the wall, and I understood: The year before, on a cold night, I had painted a mural there, of a hearth with a pleasant fire. It was no real fireplace, for in my poverty I lacked such a luxury, but I had pretended one in paint—well enough that it gave me an impression of warmth on many nights, it fooled me very pleasantly. But it had not warmed the wooden thing, and the thing had resorted to making its own fire, a real fire, right in the middle of the room.

“You might have killed people! Burned down all Collodi!” I yelled. And paused, then, in wonder: “How is it that you speak?”

“I talk! Yes, this is talking. I like it. The taste of words in my mouth.”

“Oh, terrible!” I said.

“But look at my feet! My feet are gone!”

“What a shame the flames climbed no higher,” I replied, for I admit I was most upset. “What a shame you are not all ash. What trouble you cause, ungodly object!” Was I cruel to the creature? Put yourself in my shoes. (I, who once had shoes.) Who would not be? I weep for it now.

“I have no feet,” it cried. “None at all. No feet!”

“Now where shall you run to?”

“Nowhere. I cannot!”

“It is your own fault. To play with fire! You are wood, you know! Remember that!”

“Daddy!”

“No! You are a thing, not a being,” I told it. “Lines must be drawn.”

“I am a boy,” it creaked.

“No!”

“I am!”

“You are a toy, a wooden plaything. You are for people to use as the y please, and then to put down as they please. No opinions for you. No complaints.”

There was a silence then, a gap, until it screaked its question: “How, then, may I be a boy?”

“You may not. You must not consider it.”

“I tell you I shall be. I wish it!”

“See there, object, see that hook there? That is your hook. That is where you belong, alongside my tools and pieces. My mug. My pan.”

My shaking hands. I found a screw eye.

“What is that?” it asked.

“This is a metal loop with a screw end, you see.”

“What is it for?”

“It is most useful. If something has this attachment, then I can, for example, hang it from a hook. That hook there, for example. Turn around, please.”

“What are you doing?”

“It shan’t take but a moment.”

I held him again, placed the end of the loop between his narrow shoulders.

“Ow! It hurts!”

“Come now.”

“Ow!”

“A few more turns. There, then.”

“What have you done to me?”

“Now you shall learn your place.”

I heaved it up upon the hook and there it dangled . Kicking at the wall. Clack. Clack. Thump. Something like a hanged man.

“Let me down!”

“No, I shall not. Be silent.”

“What a thing to do to your own son!”

“You are no son but a puppet.”

“I am, Babbo. I am.”

“Little boys go to school, little boys sleep in beds, little boys go to church, little boys climb trees. And you, doll, were a tree. Learn your place.”

***

In the hours we had together, we played our game. At times, I allowed it. It liked that best of all.

“What is a human?” it asked.

“I am a human.”

“Teach me to be one.”

I could not convince it by words. I must show, I must demonstrate.

“If you’re to be a child, you must sit up.”

“There then.” And it did it, creaked into position.

“That is the least of it. You must also be good. Or else the stick.”

“Well, and what then?” it said.

“Say your prayers.”

“I’ll do it.”

“Very well—let me hear you.”

“Dear father, beloved Babbo, unhappy Daddy, please unlock the door. Amen.”

“I can’t let you out. You’ll run away.”

“I shall not. I promise.”

I observed the nose. It moved not. To be certain, I measured it. Four inches and a little bit. Child.

We carried on with our game.

“Children go to school.”

“Then I shall go to school.”

“They learn their lessons.”

“Then so shall I.”

“It would be ridiculous!” I said, laughing at the idea. But look there: a seed growing in my head.

“I would like to try. Please, sir.”

“You will run away.”

“No, no, I shall not.”

I observed. I measured. Inches four and a little bit.

“No,” I said finally.

“Help me! You can help, sir. Father, you can, I know.”

I could come up with no other response, so I did the only thing I could think of: I locked him in and I went outside. Where I could think. I was having ideas.

As I walked, I confess, I began to dream of money—a deal of money—that might suddenly be within reach. And why not? I deserved it, didn’t I, after all these lean years? I was the maker, I alone. But first I had some things to do. To get more money you must start by investing a little, I thought, so I took my own coat down to Master Paoli’s store—the greatest shop in all Collodi, almost anything may be purchased there—and sold it. With the money from the coat, I bought from Paoli some secondhand children’s clothes, and something else: a schoolbook. And then, fool that I was, I carried them all home.

We clothe our children so they may fit in, do we not? I showed him the clothes and his wooden eyes seemed to grow. He reached out and put them on; a little baggy, but they fit well enough. The sight of him clothed made my eyes itch. So much more convincing wearing the pair of old shorts, the collarless shirt. How splendid to see a stick turning the pages of a schoolbook. Yes, I thought, there was a trial: If I brought this woodlife to school, how would the children react? They’d not keep quiet, that was certain. They’d spread the news. The wooden child would become famous. First in Collodi, then throughout the world. And because of it, I too.

It would be the most wonderful business.

I had no understanding of the danger, not yet.

I took the screw eye from out of his back. “You no longer need this, my good boy.” And so he—I began to call him he you see, I went that way at last—and so, yes, he would go into the world after all, this thing of mine, my mannequin.

“It is time for you to go to school, my little boy of pine.”

“Father, what is my name? I should have a name if I’m going to school.”

“Puppet.”

“That is not a name.”

Wooden monster, I thought. Haunted spirit begot from loneliness. Impossible life, miracle and curse. Specter stump. But I said, “Wood chip, wood louse, sawdust, shaving, lumber life, kindling, pine pit—yes, there must be some pine, some Pino, in the name. Pinospero, Pinocido, Pinorizio, no, just plain Pino. Only pine, for that is you, or for fondness, to add a nut, a noce.… Pinocchio.

“Pinocchio?” he asked, excited.

“Yes, then, Pinocchio.”

“Pinocchio!”

“It is time for school, Pinocchio.”

“Goodbye, Babbo.”

“Goodbye, Pinocchio.”

I opened the door, how the light rushed in through the oblong, and I watched him walk out into the world. To see him so illuminated! Down the street he went, out of my reach, toward the schoolhouse.

I watched the breeze ruffle his clothes, as if the wind itself supposed he was one of us. To think I had made such a creature, that set forth this way on its own feet! How well, I thought, I shall be known for it. How celebrated—the creator of life. I shall be rich, I think. I watched him go, his wooden gait, his upright form trying to be flesh. What a thing. He walked as if he belonged to the world. I did not call him back, and off he creaked, as I watched. It quite broke my heart. To see him so excited, with his schoolbook, as if he were equal to any other. Off, impossible thing! Yes, off to school.

And he never came back.

How I waited. But he never. I’d lost my life. All company gone.

I have not seen him since. Unless in a dream be counted.

Though I dedicate my life to recovering him.

From The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey. Copyright 2021 © by Edward Carey. Published by Riverhead Books. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.